第四章:兒童肺炎

重點提要

兒童肺炎指引內容分為流行病學、經驗性治療(細分為住院準則、門診治療、住院治療),及已知病原菌之治療。提供六個表格,分別敘述住院準則,呼吸窘迫的徵象,門診病患經驗性口服抗生素治療,住院病人經驗性抗生素 治療,已知病原菌之抗生素治療,及抗生素治療之建議劑量。流行病學增加肺炎鏈球菌疫苗接種後的情況及致病原改變,經驗性治療增加住院準則並分門診及住院的治療,已知病原菌之治療則根據新的臨床與實驗室標準協會(Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institutes, CLSI)的判讀標準來制定。與國外不同處在於流行病學,經驗性治療強調典型與非典型肺炎選擇藥物的不同。

主編:劉清泉

副編:黃玉成

4-1 流行病學

加入書籤

在過去的這二十年裡,發展中國家和新興工業化國家的兒童社區型肺炎(community acquired pneumonia, CAP)的病因產生了顯著的改變 [1], 在眾多造成影響的因素中,b 型流感嗜血桿菌結合型疫苗(Haemophilus influenzae type b conjugate vaccine, HibCV)和肺炎鏈球菌結合型疫苗(pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, PCV)這兩種疫苗的上市使用是不能被忽略的 [2][3],特別是在已經將上述兩種疫苗納入常規疫苗接種時程的國家。在台灣結合型疫苗的演進歷程中,b 型嗜血桿菌結合型疫苗於 1996 年首次 引進市場供自費接種,而 DTaP-Hib-IPV 五合一疫苗自 2010 年起被列入幼兒常 規疫苗接種。至於肺炎鏈球菌結合型疫苗,則是在 2005 年和 2011 年分別推出自費 7 價(PCV7)和 13 價的肺炎鏈球菌結合型疫苗(PCV13)在台上市。根據衛生福利部疾病管制署傳染病防治諮詢會預防接種組的建議,台灣於 2013 年開始優先針對出生滿 2 歲至 5 歲的幼童實施 PCV13 公費接種計畫,並自 2014 年擴增提供滿 1 歲至 5 歲的幼兒公費接種 PCV13。從 2015 年起 PCV13 被列入幼兒常規疫苗接種政策,採「2+1」的時程於出生滿 2、4 個月時各接種一劑基礎劑,滿 1 歲時再接種一劑追加劑。儘管針對 b 型嗜血桿菌以及肺炎鏈球菌的預防接種規劃日益完善,台灣的全國傳染病監視報告(National Notifiable Disease Surveillance System, NNDSS)直到 1999 年和 2007 年才分別納入侵襲性 b 型嗜血桿菌感染症和侵襲性肺炎鏈球菌感染症(invasive pneumococcal disease,IPD)的監控,以致我們仍然缺乏對於兒童社區型肺炎病因的完整流行病學資料。迄今為止,有兩項關於造成肺炎的細菌和病毒的本土研究:一項是在 2001 年至 2002 年之間尚未引 進肺炎鏈球菌疫苗的時期針對一間醫學中心肺炎住院病童進行的調查 [4],另一項是由台灣小兒感染症聯盟(Taiwan Pediatric Infectious Disease Alliance,TPIDA)主持,在 2010 年 11 月至 2013 年 9 月期間針對八間醫學中心的肺炎住院病童做的調查(PCV13 公費接種計畫始於 2013 年 3 月,此研究收案至公費接種計畫開始實施後的 6 個月就結束)[5]。在尚未全面公費施打肺炎鏈球菌疫苗前,肺炎鏈球菌佔前一項研究中 209 例兒童社區型肺炎病例的 41.1%,佔後一項研究中 1032 例兒童社區型肺炎病例的 31.6%。與西方國家不同,黴漿菌肺炎(mycoplasmal pneumonia)在未滿 19 歲台灣兒童的患病率似乎較高(分別佔上述兩項研究中 36.8% [4] 和 22.6% [5] 的病例)。值得注意的是,之前的研究指出在台灣大約 12 至 23%的黴漿菌對巨環黴素類(macrolide)抗生素是有抗藥性的 [6][7]。在全面公費常規接種 b 型嗜血桿菌結合型疫苗(現併入 DTaP-Hib-IPV 五合一疫苗)和 PCV13 的情況下,病毒性的病原體可能逐漸成為造成嬰兒和學齡前兒童社區型肺炎的主要原因,而黴漿菌感染的比例則隨著年齡增加而上升 [8][9]。台灣自 2015 年開始全國幼兒常規接種 PCV13,在三年後的今天要評估 PCV13 接種對台灣兒童社區型肺炎病因的長期影響可能還為時過早。然而,根據其他已常規接種 PCV13 多年的國家的經驗,我們也許可以假設病原體之間的消長也會出現類似的變化。針對本土流行病學的進一步研究將可以幫助我們更好地處理兒童社區型肺炎。

4-2 兒童肺炎經驗性治療

加入書籤

一、病人評估及住院準則

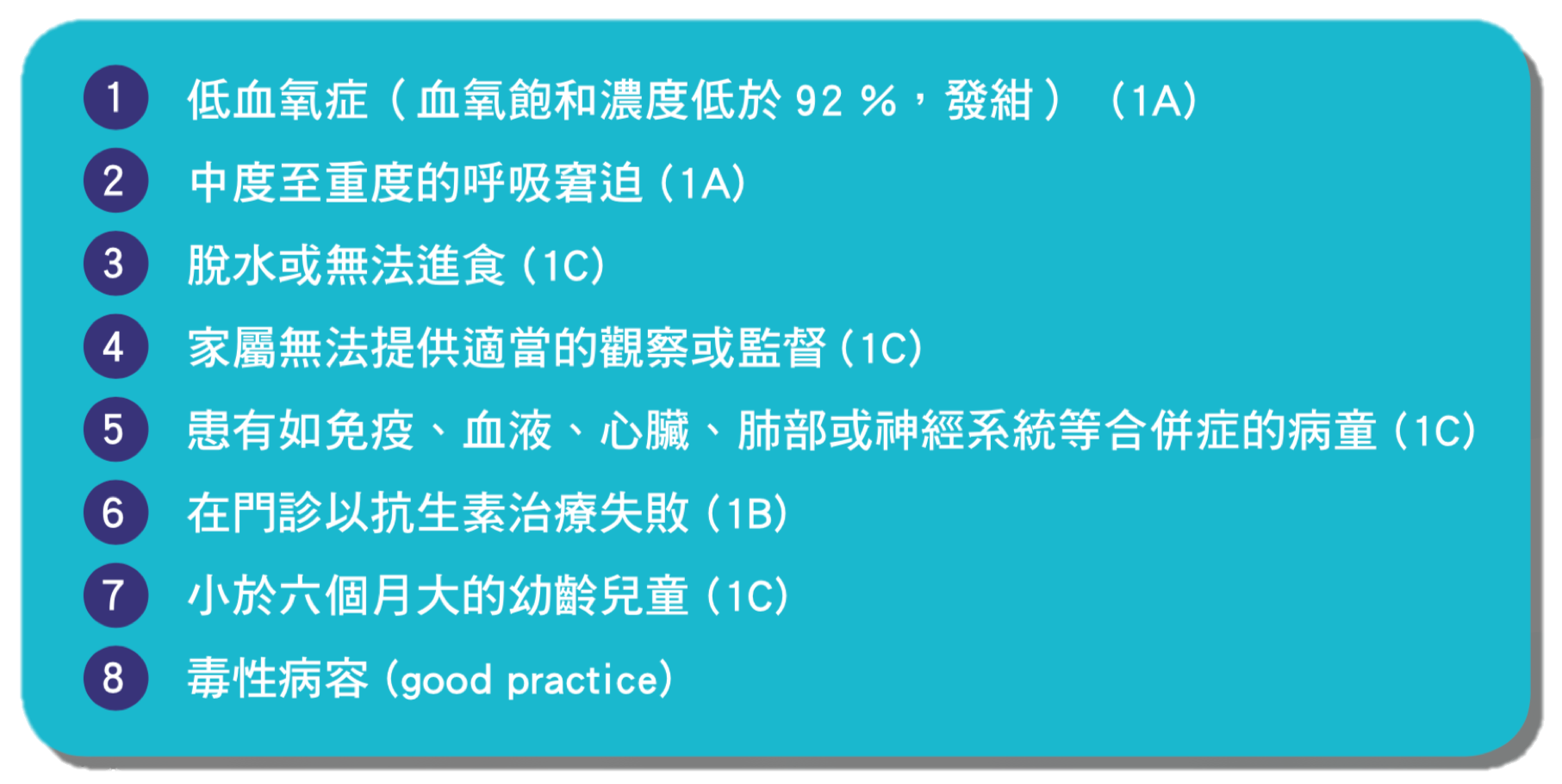

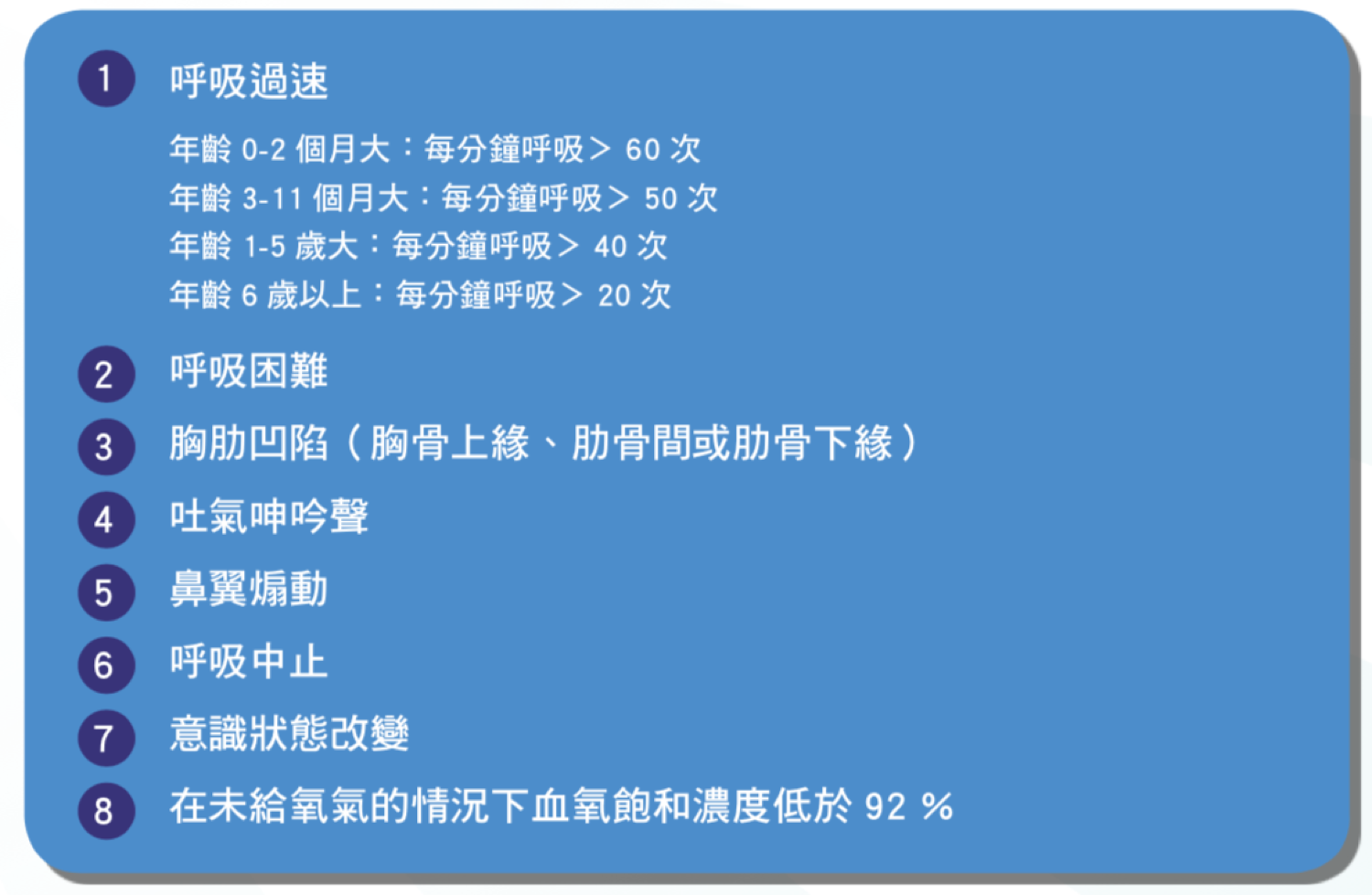

截至目前為止,還沒有一個經過驗證的評分系統能夠有效地預測得到肺炎的兒童是否必須住院治療。然而多數的專家以及學會團體都會建議,只要得到肺炎的兒童或嬰兒發生呼吸窘迫都應該要住院治療(見表 4.1 及表 4.2)。兒童所謂的毒性病容(toxic appearance)是一種需要經驗輔助判斷的臨床描述,這種描述雖然屬於主觀認定,也沒有很精確的定義,但某些特定的症狀及徵象可以提醒臨床醫師毒性病容的存在,其中包含膚色的異常變化(如蒼白、發紺等)、倦怠缺乏活力、無法安撫的躁動不安、意識改變或認知障礙、持續過速或過慢的心跳、呼吸,或是末梢微血管回沖時間延長。若是兒童出現毒性病容,暗示著即將發生失衡的生理代償,所以如同表 4.1 中列出的其他條件,毒性病容一般被視為兒童肺炎接受住院治療的適應症 [10]。在眾多的臨床指標當中,低血氧症(hypoxemia)目前已確立是造成兒童呼吸道疾病預後較差的危險因子,因此我們建議得到肺炎的兒童應該要測量血氧飽和濃度。過去的研究顯示,得到非嚴重肺炎(此指在未合併下胸壁凹陷、或年齡未滿兩個月大呼吸速率超過每分鐘 60 次、或大於兩個月大呼吸速率超過每分鐘 50 次)的兒童,若是初次測得的血氧飽和濃度就小於 90%,幾乎可以預期該病童的院外抗生素治療會失敗 [11]。目前普遍共識認為過去 身體健康的兒童得到社區型肺炎時,若在未給氧氣的情況下血氧飽和濃度低於 90%,該病童應該住院接受治療;然而有其他的意見認為兒童的血氧飽和濃度若是低到 93% 就應該住院治療 [12]。

病童若有潛在的疾病或共病症(comorbidity)也是併發肺炎的危險因子之一。已經有眾多的研究顯示住院治療肺炎的兒童中相當比例的病人有潛在的共病症:如免疫系統疾病、血液系統疾病、心臟疾病,或慢性肺部疾病 [13][14]。由於肺炎往往造成原本的潛在疾病惡化,反之亦然;因此我們建議要更謹慎地評估這一類病童住院治療的需求。

較小的年齡也是增加肺炎嚴重度及住院需求的危險因子。先前的研究嘗試找出得到嚴重肺炎的兒童中哪些族群以口服抗生素治療後會失敗,他們發現兒童的年齡是最重要的臨床預測指標之一(尤其是當兒童的年齡不到六個月大時差異更 為顯著)[15]。基於上述治療失敗的風險以及幼兒感染肺炎時較有機會產生合併症,我們建議若是懷疑未滿六個月大的嬰兒得到細菌性社區型肺炎時應住院接受治療 [16]。此外,兒童若有脫水、嘔吐無法進食,或是無法吞食口服藥物等狀況時也應該考慮住院治療。兒童若接受院外口服抗生素治療後病情沒有明顯進步或者進一步惡化出現呼吸窘迫,也會需要住院治療。再者,若病童有心理社會、家庭或經濟層面等問題,導致醫囑遵從性不佳或者無法按時回診追踪,那麼這樣的病童也應該住院接受治療 [10]。

二、兒童社區型肺炎門診治療建議

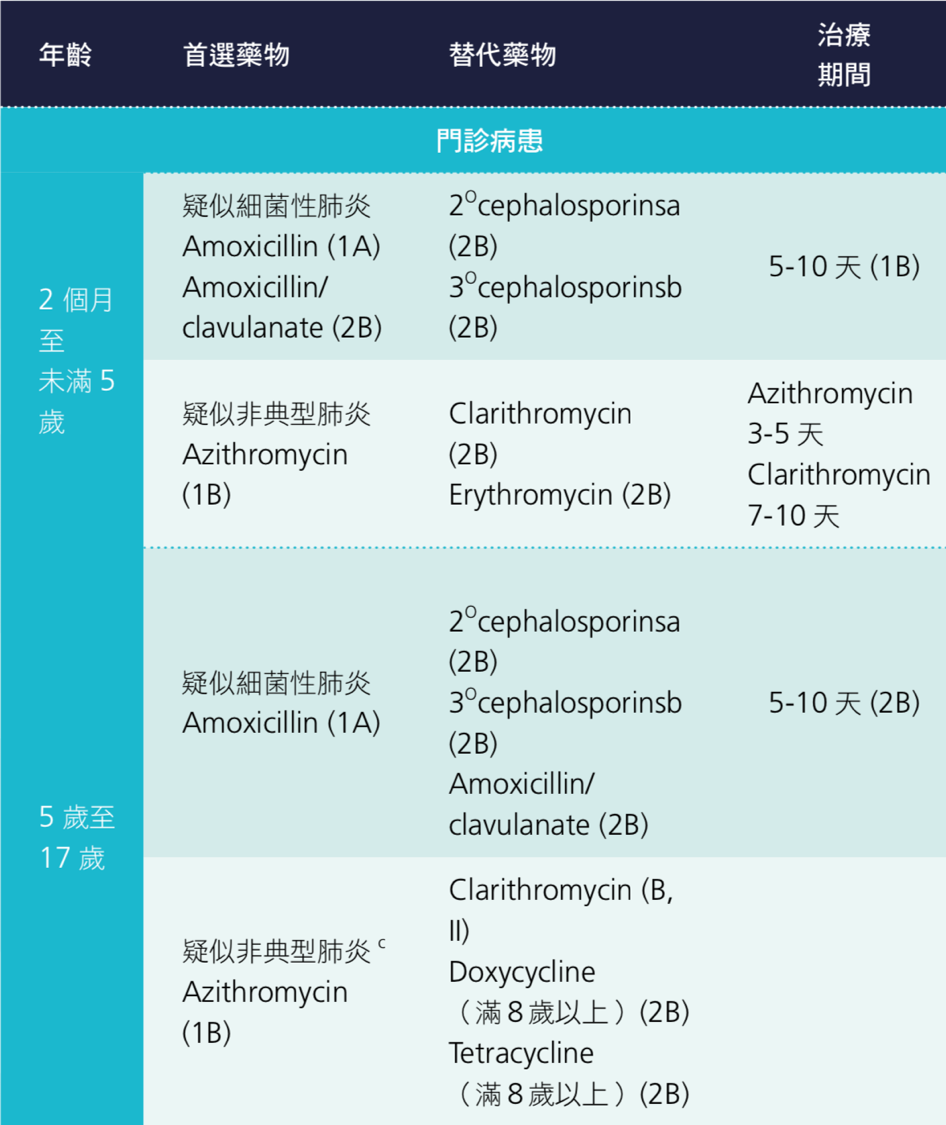

詳見 表 4.3

兒童感染社區型肺炎時,門診治療的首選藥物為 amoxicillin [17][18][19][20][21][22]。考量到肺炎鏈球菌可能的抗藥性,建議劑量為 amoxicillin(90 mg/kg/day,分一天 2~3 次給予)[17][23][24]。替代藥物可選擇 amoxicillin/clavulanate 或第二代 cephalosporin。若為嚴重 penicillin 過敏,則選用 levofloxacin, moxifloxacin 或 linezolid 代替 [17][18][25][26]。學齡期之兒童(≥ 5 歲),若懷疑致病菌為非典型細菌,則建議使用 macrolide 作為經驗性用藥(macrolide 的選擇列在表 4.3) [17][18][25]。

當病人的感染原因無法判定為典型或非典型細菌感染時,是否同時併用 β-lactam 和 macrolide 治療目前尚無定論。某一回溯性研究顯:對於在門診接受社區型肺炎治療的學齡期以上兒童,同時給予 β-lactam 及 macrolide 合併治療可以降低治療失敗率,但在學齡前期兒童則無此現象 [27]。另 2017 年有一前 瞻性實驗,研究臨床治療失敗率與非典型細菌(包括黴漿菌(M. pneumoniae)、肺炎披衣菌(C. pneumoniae)和鸚鵡熱披衣菌(C. trachomatis))造成的急性感染之間的關係。其受試對象為年紀 2~59 個月的兒童,受試兒童全部以 amoxicillin 作為經驗性治療之藥物。結果發現:不管後來是否證實為非典型細菌感染,在治療第 2 天與第 5 天之治療失敗率與替換 amoxicillin 之機率,並無統計上顯著差異。該 作者因此建議對於年齡 2~59 個月大門診治療之社區型肺炎病人,不需要經驗性使用 non-β-lactam 抗生素作為第一線用藥 [28]。由上述研究歸納,經驗性的使用 β-lactam/macrolide 合併治療,在 5~18 歲兒童可能是有好處的,但在 5 歲以下幼兒則較無證據顯示合併治療的好處。

關於治療時間,雖然 10 天抗生素的療程是最為廣泛被研究與接受的,但新的證據顯示,使用較短的療程可能一樣有效。有統合分析研究發現,3 天的療程 效果並不差於 5 天 [29][30]。不過該分析原始研究對象皆是以 WHO 肺炎定義作為診 斷,並無加上胸部 X 光證明,所以可能有些兒童實際上為病毒性肺炎。另一在以色列做的前瞻性研究,則發現以高劑量的 amoxicillin(80 mg/kg/day)治療門診社區型肺炎之兒童,5 天的療程效果不亞於傳統 10 天,但 3 天的療程則會導致高失敗率 [31]。綜合以上,建議以 5~10 天抗生素作為門診社區型肺炎病人之治療時間。

三、兒童社區型肺炎住院治療建議

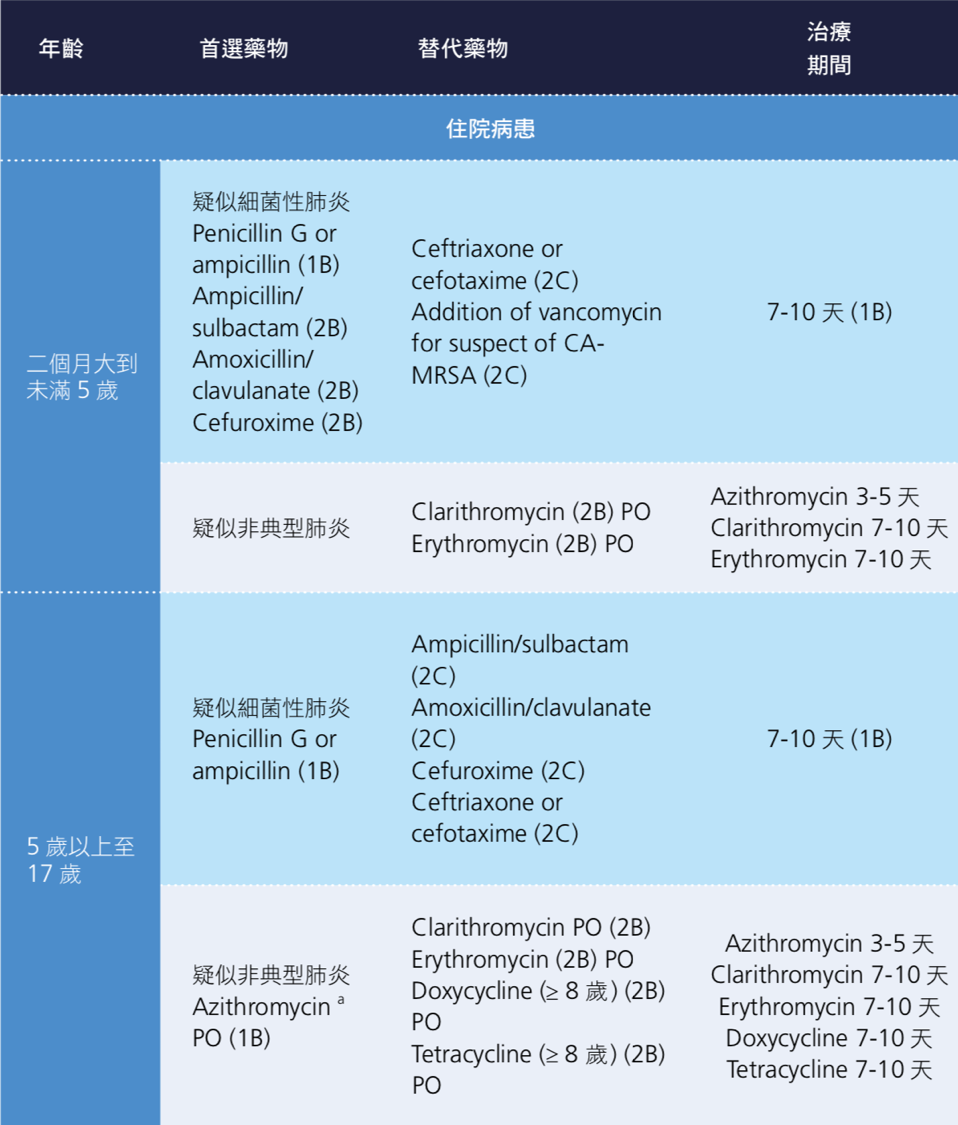

詳見 表 4.4

由於學齡前的兒童感染社區型肺炎時,多數是病毒性感染引發的肺炎,因此這一類的病人不應常規使用抗生素治療 [32],然而當病人因被懷疑細菌性感染所引發的肺炎而住院時,因為疾病病情較為嚴重,因此仍建議使用針劑的抗生素治療, 以確保病人能夠有足夠的抗生素血液治療濃度來殺菌,經驗性抗生素治療應涵蓋大部份會引起下呼吸道感染的細菌,而抗生素的使用也要針對本土微生物流行病學來調整,才能夠更針對社區型肺炎的致病菌做治療。在尚未全面施打肺炎鏈球 菌疫苗的時代,肺炎鏈球菌是引發兒童社區型肺炎最常見的細菌,若未能妥善的治療也較容易合併嚴重的併發症 [4][33][34]。Penicillin G 是針對肺炎鏈球菌最窄效但也是最有效的抗生素,針對 penicillin 具有感受性(susceptible)或中間性感受性(intermediate susceptible)的肺炎鏈球菌仍建議使用高劑量 penicillin G (400,000 U/kg/day,每 4-6 小時給予)或 ampicillin(150-200 mg/kg/day,每 6 小時給予)為治療的首選藥物。

台灣在 2013 年針對 2 歲至 5 歲的兒童全面公費補接種一劑 13 價肺炎鏈球 菌結合型疫苗(PCV13)之後,該年齡層兒童的侵襲性肺炎鏈球菌感染症(invasive pneumococcal disease,IPD)發生率從 2011 至 2012 年(補接種疫苗前)的每十萬人年 22.8 個個案下降至 2013 年(疫苗補接種當年度)的每十萬人年 11.9 個個案。隨著 PCV13 的公費補接種在 2014 年向下擴大至當年度 1 歲以上的兒童,該新增族群(1 歲至 2 歲的兒童)的 IPD 發生率也從 2013 年的每十萬人年 11.4 個個案,下降至 2014 年每十萬人年 7.1 個個案 [35]。在 2009 至 2014 年之間,血清型 19A 一直都是未滿 5 歲兒童 IPD 中最常見的血清型 [36][37],但在實施 PCV13 的公費補接種後,可觀察到血清型 19A 相關的 IPD 發生率從 2011 至 2012 年間的每十萬人年的 12.9 個個案下降到 2013 年的每十萬人年的 6.0 個個案 [36]。在開始 PCV13 接種之後,PCV13 無法涵蓋的血清型如 23、13 和 35 相關的 IPD 個案陸續增加,意味著血清型置換現象(serotype replacement phenomenon)的出現,而整體來說 IPD 的發生率是持續下降的。考量到血清型 19A 肺炎鏈球菌仍是目前疫苗施打後突破性感染最常見的血清型,以及它高度抗藥性的特質,臨床醫師必須視情況使用 ceftriaxone 或 cefotaxime 作經驗性抗生素治療,因為就對 penicillin 有抗藥性的菌株而言,penicillin 在體外試驗(in vitro)的治療效果不如 ceftriaxone 或 cefotaxime [38]。

台灣自 2010 年開始便將包含了 b 型流感嗜血桿菌結合型疫苗在內的五合一疫苗(DTaP-Hib-IPV)納入幼兒常規疫苗接種。根據疾管署全國傳染病監視報告 (National Notifiable Disease Surveillance System,NNDSS)顯示,自 2005 年起每年台灣本土的侵襲性 b 型嗜血桿菌感染症通報個案都小於 20 例,由此可 見 b 型嗜血桿菌己不再是引發兒童侵襲性感染或社區型肺炎常見的致病菌 [4]。但是就無法分型的流感嗜血桿菌(non-typeable H. influenza, NTHi)而言,雖然它較少在一般正常兒童身上引起肺炎,但是對有慢性肺部疾病或阻塞性肺病變的兒童,就有可能引起嚴重的下呼吸道感染,而當 NTHi 可能是病童肺炎的致病原時,由於台灣的 NTHi 多數帶有可分解乙內醯胺(β-lactam)的分解酶(β-lactamase) [39],因此在抗生素的使用上就需要用到第二代的頭孢子素(2nd generation cephalosporin 如 cefuroxime 或 cefaclor)或者是 β-lactam 合併 β-lactamase inhibitor 類的抗生素(如 ampicillin/sulbactam 或 amoxicillin/clavulanate)。

黴漿菌是台灣兒童社區型肺炎第二常見的致病細菌 [40],但是大部份的文獻報導多著重在學齡兒童的症狀表現。之前的研究指出因肺炎住院的學齡兒童接受 β-lactam 加上巨環黴素 (macrolide) 的合併治療比起單獨使用 β-lactam 治療 的兒童住院天數較短,但 14 天內再次住院的機率與單獨使用 β-lactam 治療的 兒童差不多 [41]。在學齡前的兒童使用 β-lactam 合併 macrolide 的治療並不會有明顯的好處,而且可能會增加醫療費用 [42]。從 2010 年 1 月至 2012 年 6 月,美國學者 Williams 在美國三間兒童醫院做了一份以族群為基礎的多中心前贍性研究,在此份研究當中他比較了單獨使用 β-lactam 以及同時併用 β-lactam 和 macrolide 這兩種治療方式對兒童社區型肺炎住院天數的影響。在這項研究中單 獨使用 β-lactam 的組別有 1019 位兒童,同時併用 β-lactam 及 macrolide 的組別有 399 位兒童,而兩組的住院天數並沒有統計上顥著的差異。雖然說此篇研究的兒童平均年齡偏小 (年齡中位數:27 個月大,四分位距 12~69 個月大),作者仍認為對因社區型肺炎住院的兒童經驗性地同時併用 β-lactam 和 macrolide 並沒有優於單獨使用 β-lactam [43]。雖然根據國外的文獻資料顯示,兒童社區型肺炎的住院病患不應該常規性地以同時併用 β-lactam 和 macrolide 做 為經驗性療法,但就台灣小兒感染症臨床試驗聯盟 (TPIDA) 所做的兒童社區型肺炎研究顯示,雖然五歲以上的兒童是黴漿菌肺炎發生率較高的年齡層,但五歲以下兒童得到黴漿菌肺炎時,卻會比五歲以上的兒童有較長的住院天數、較高的比例需要加護病房照顧,甚至於較多的合併症 [40],因此雖然五歲以下兒童並不建議常規使用 macrolide 做為經驗性治療,但仍應慬慎評估病人可能的致病菌,對於可能的黴漿菌肺炎仍經積極的治療,以減少相關併發症的產生。

由於細菌性肺炎與非典型肺炎在臨床表現上有相當的重疊,所以針對懷疑為細菌性社區型肺炎的兒童,如果沒有臨床、實驗室或影像學證據可與非典型社區型肺炎做明確的區分,則可合併使用乙內醯胺(ß-lactam)類抗生素加上巨環黴素(macrolide)類抗生素作為經驗性處方予以治療,之後視臨床證據再做調整。

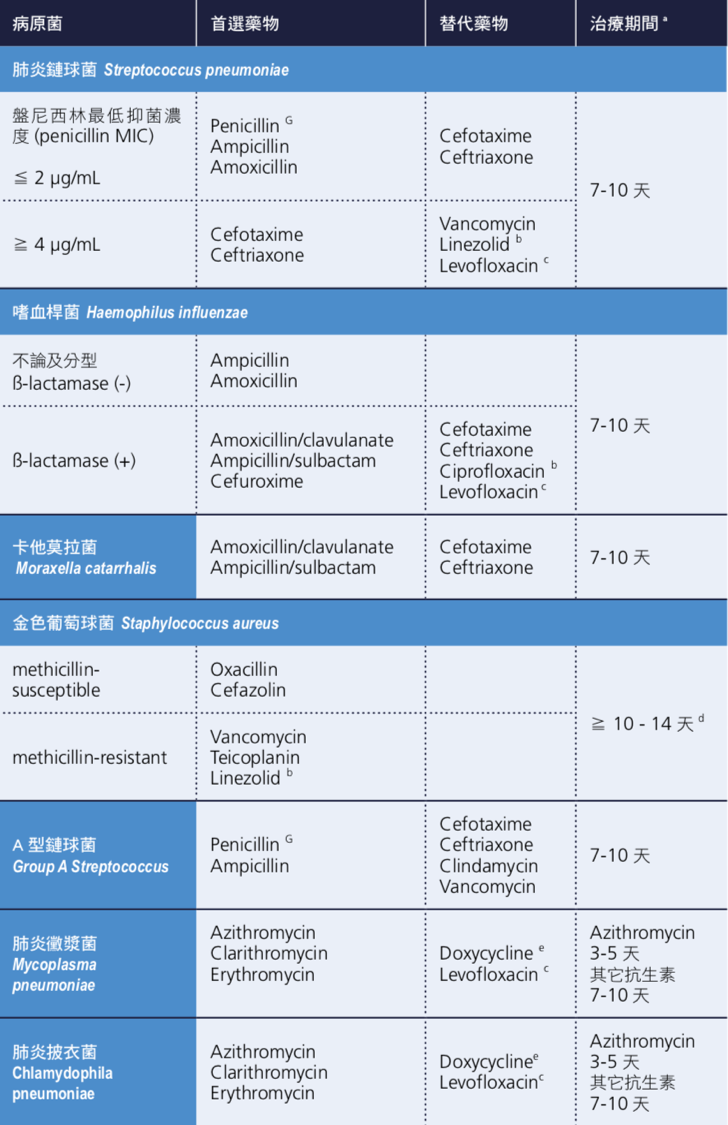

4-3 兒童肺炎已知病原菌之治療

加入書籤

雖然針對得到社區型肺炎的兒童做的血液培養很少能分離出致病菌 [44],但是為了防止致病菌產生抗藥性,一旦血液培養有長菌而抗生素敏感試驗也有結果,必須盡快根據其結果調整原本的抗生素治療 [45]。

根據 2008 年版本臨床與實驗室標準協會(Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute,CLSI) 的 準則,針對肺炎鏈球菌(Streptococcus pneumoniae)引發的非腦膜炎疾病,盤尼西林(penicillin)的最低抑菌濃度 (minimal inhibitory concentration,MIC)標準已更改為:MIC ≤ 2 μg/mL 時屬於對 penicillin 有感受性(susceptible)的菌株,MIC = 4 μg/mL 為中度抗藥性(intermediate)菌株,而 MIC ≥ 8 μg/mL 時屬於對 penicillin 有抗藥性(resistant)的菌株 [46]。台灣疾病管制署從 2007 年開始監測侵襲性肺炎鏈球菌感染症(invasive pneumococcal disease,IPD),若以上述 CLSI 準則不分年 齡層檢視其中造成 IPD 的菌株,就非腦膜炎(non-meningitis)疾病的標準來說,對 penicillin 有抗藥性的 IPD 菌株比例從 2008 年的 6.4% 來到了 2016 年的 1.9% [47]。對於其他經常使用於兒童肺炎鍊球菌感染的抗生素如 amoxicillin 及 cefotaxime 等藥物,這些造成 IPD 的菌株對其具感受性的比例也在 2012 年之後 有上升的趨勢 [47]。台灣從 2013 年開始 13 價肺炎鏈球菌結合型疫苗(PCV13)的公費補接種計畫,抗藥性肺炎鏈球菌的比例下降似乎與涵蓋在 PCV13 內具高度抗藥性的血清型 19A 減少有關。從開始監測 IPD 以來,這些菌株中對 fluoroquinolone 或 vancomycin 有抗藥性的比例一直很低。在接種肺炎鏈球菌結合型疫苗的世代,肺炎致病菌的變化以及 CLSI 對於肺炎鏈球菌抗藥性定義的 調整都影響著治療兒童社區型肺炎的抗生素選擇 [8][46]。

B 型流感嗜血桿菌(Haemophilus influenzae type b,Hib)在兒童造成的侵襲性感染症自從幼兒常規接種 DTaP-Hib-IPV 五合一疫苗之後變得很少見。無法分型的嗜血桿菌(non-typable Haemophilus influenzae, NTHi) 感染則在增加,這也是流感兒童的急性中耳炎重要致病菌之一。根據台北馬偕醫院一個針對從中耳積液培養出細菌做的研究,無法分型的嗜血桿菌對 amoxicillin 有感受性的比例在過去十年 來由 30% 降至 20%,這可能跟會產生乙內醯胺分解酶(β-lactamase)的菌株增加有關 [48]。在台灣若考量到 NTHi 造成的兒童社區型肺炎,amoxicillin 可能已經不是一個可靠的經驗性抗生素。相對而言,NTHi 對 amoxicillin/clavulanate 有抗藥性的比例近十年來則維持在 20~25% 之間,因此在治療 NTHi 造成的兒童社區型肺炎,amoxicillin/clavulanate 是較為適當的選擇 [48]。

根據台灣醫院的研究,絕大部分(97.8%)的卡他莫拉菌 (Moraxella catarrhalis) 會產生 β-lactamase,而對於 amoxicillin 具有抗藥性 [49]。數個藥物動力學的研究都顯示高劑量的 amoxicillin/clavulanate、cefotaxime 或 ceftriaxone 可以有效治療此病菌 [50]。金黃色葡萄球菌(Staphylococcus aureus) 在兒童病患可能會造成嚴重的肺炎及併發症,尤其是在流行性感冒病毒流行的季節。由於社區型抗藥性金黃色葡萄球菌(community associated methicillin- resistant S. aureus,CA-MRSA)過去十年在台灣益發盛行,S. aureus 造成的兒童社區型肺炎治療失敗率也越來越高。治療 CA-MRSA 的首選藥物為 vancomycin、teicoplanin 及 linezolid。我們建議當 S. aureus 對 vancomycin MIC ≧ 2 μg/mL 時,應以 linezolid 為首選抗生素。

肺炎黴漿菌(Mycoplasma pneumoniae)很難由呼吸道分泌物中培養出來。治療 M. pneumoniae 的首選藥物為巨環黴素(macrolide)類的藥物。然而,於 23S rRNA 特定部位發生的點突變會導致 M. pneumoniae 對於 macrolide 產生高 度抗藥性 [51]。在 2010~2011 年台灣因社區型肺炎住院之兒童的研究中發現,M. pneumoniae 對於 macrolide 出現抗藥性的比例為 12~23%,明顯低於周圍亞洲其他國家如中國、日本及南韓 [6][7][52]。四環黴素(tetracycline)類及氟奎諾酮 (fluoroquinolone) 類的抗生素可用於治療產生 macrolide 抗藥性的 M. pneumoniae,然而這些替代藥物對幼童可能造成的副作用往往限制了臨床上的使用 [53]。事實上在最近的一些研究顯示,短期使用 doxycycline 治療未滿 8 歲兒童的感染並不會造成牙齒琺瑯質的染色 [54]。在使用 tetracycline 或 fluoroquinolone 治療兒童疾病之前,臨床醫師必須謹慎衡量治療的好處及可能的副作用。若病人在使用 macrolide 治療至少 48 至 72 小時之後仍持續發燒,或是追蹤胸部X光顯示肺炎有影像學上的惡化,則可考慮使用如 tetracycline 或 fluoroquinolone 等替代藥物治療黴漿菌肺炎 [55]。

過去的文獻並沒有適合的隨機分派對照研究(randomized controlled study)能決定兒童社區型肺炎最適合的治療期間。以大部分的專家及教科書建議,針對沒有併發症的兒童社區型肺炎使用 7~10 天的抗生素治療是合適的 [45][50]。然而一旦有肺炎併發症如敗血症、轉移他處的感染、壞死性肺炎、肺膿瘍或肋膜腔積膿產生時,治療期間必須延長。若有膿瘍或積膿時須考慮外科介入治療。由 S. aureus 造成的兒童社區型肺炎治療期間往往須超過 10~14 天,實際的治療期間在不同個案間差異極大,取決於臨床疾病嚴重度及是否發生肺炎併發症 [56]。

表 4.1 住院準則

表 4.2 呼吸窘迫的徵象

表 4.3 兒童社區型肺炎經驗性口服抗生素治療(適用於門診病患)

表 4.4 兒童社區型肺炎住院病人經驗性抗生素治療(若無特別標註 PO 則皆為靜脈注射藥物)

表 4.5 兒童社區型肺炎已知病原菌之治療

表 4.6 兒童抗生素劑量建議

| 抗生素種類 | 劑量建議 |

|---|---|

| Amoxicillin | 90 mg/kg/day PO 分為 2-3 劑給予;最高劑量每日 4,000 mg |

| Amoxicillin/clavulanate | Amoxicillin 90 mg/kg/day PO 分為 2-3 劑給予;最高劑量每日 4,000 mg |

| Amoxicillin/clavulanate | Amoxicillin 100-200 mg/kg/day IV q6-8h;最高劑量每日 4,000 mg |

| Ampicillin | 150-400 mg/kg/day IV q6h;最高劑量每日 12,000 mg a |

| Ampicillin/sulbactam | Ampicillin 150-400 mg/kg/day IV q6-8h;最高劑量每劑 2,000 mg |

| Azithromycin | 10 mg/kg qd 給予 3 天(最高劑量每日 500 mg);或第 1 天給予 10 mg/kg qd(最高劑量每日 500 mg),第 2-5 天 5 mg/kg/day qd(最高劑量每日 250 mg) |

| Cefaclor | 20-40 mg/kg/day PO 分為 3 劑給予;最高劑量每日 1,000 mg |

| Cefazolin | 100-150 mg/kg/day IV q6-8h;最高劑量每劑 2,000 mg |

| Cefixime | 8 mg/kg/day PO 分為 1-2 劑給予;最高劑量每日 400 mg |

| Cefotaxime | 150-200 mg/kg/day IV q6-8h;最高劑量每劑 2,000 mg |

| Ceftibuten | 9 mg/kg/day PO qd;最高劑量每日 400 mg |

| Ceftriaxone | 50-100 mg/kg/day IV q12-24h;最高劑量每日 2,000 mg b |

| Cefuroxime | 100-200 mg/kg/day IV q6-8h;最高劑量每劑 1,500 mg |

| Cefuroxime axetil | 20 to 50 mg/kg/day PO 分為 2 劑給予;最高劑量每劑 500 mg |

| Cephalexin | 75-100 mg/kg/day 分為 3-4 劑給予;最高劑量每日 4,000 mg |

| Clarithromycin | 15 mg/kg/day PO 分為 2 劑給予;最高劑量每劑 500 mg |

| Clindamycin | 40 mg/kg/day IV q6-8h;最高劑量每日 2,700 mg |

| Clindamycin | 30–40 mg/kg/day PO 分為 3 劑給予;最高劑量每日 1,800 mg |

| Dicloxacillin | 50 to 100 mg/kg/day PO 分為 4 劑給予;最高劑量每劑 500 mg |

| Doxycycline | 4.4 mg/kg/day PO 分為 1-2 劑第一天給予,後 2.2-4.4(嚴重感染 4.4)mg/kg/day 分為 1-2 劑給予;最高劑量每日 200 mg |

| Erythromycin | 40 mg/kg/day PO 分為 4 劑給予;最高劑量每日 4,000 mg |

| Levofloxacin | 年齡 6 個月至 < 5 歲:8-10 mg/kg/dose IV q12h;最高劑量每日 750 mg 年齡 ≥ 5 歲:8-10 mg/kg/dose IV qd;最高劑量每日 750 mg 年齡 6 個月至 < 5 歲:8-10 mg/kg/dose PO q12h;最高劑量每日 750 mg 年齡 ≥ 5 歲:8-10 mg/kg/dose PO qd;最高劑量每日 750 mg |

| Linezolid | 年齡 < 12 歲:30 mg/kg/day IV q8h 或 PO 給予 3 劑 年齡 ≥ 12 歲:20 mg/kg/day IV q12h 或 PO 給予 2 劑 |

| Oxacillin | 150–200 mg/kg/day IV q6-8h;最高劑量每日 12,000 mg |

| Penicillin G | 200,000-400,000 unit/kg/day IV q4-6h;最高劑量每日 24,000,000 units/day |

| Teicoplanin | 初始劑量:10 mg/kg(最高劑量 400 mg)IV q12h 給予 3 劑;維持劑量:6 to 10 mg/kg IV qd |

| Tetracycline | 25 to 50 mg/kg/day PO 分為 2-4 劑給予;最高劑量每劑 500 mg |

| Vancomycin | 40-60 mg/kg/day IV q6-8h;最高劑量每日 4,000 mg |

註解:

- a: 肺炎雙球菌 S. pneumoniae ( 最低抑菌濃度 MIC for penicillin ≦ 2 μg/mL) 時,建議劑量 150-200 mg/kg/day 分為 q6h 給予;S. pneumoniae (MIC for penicillin ≥ 4 μg/mL) 時,建議劑量 300-400 mg/kg/day 分為 q6h 給予。

- b: 對於 HIV 感染的患者,ceftriaxone 的每日最高劑量可以到 4,000 mg

參考文獻

Deantonio R, Yarzabal JP, Cruz JP, et al. Epidemiology of community-acquired pneumonia and implications for vaccination of children living in developing and newly industrialized countries: A systematic literature review. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2016;12(9):2422-40. ↩︎

Baqui AH, El Arifeen S, Saha SK, et al. Effectiveness of Haemophilus influenzae type B conjugate vaccine on prevention of pneumonia and meningitis in Bangladeshi children: a case-control study. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2007;26(7):565-71. ↩︎

Pilishvili T, Lexau C, Farley MM, et al. Sustained reductions in invasive pneumococcal disease in the era of conjugate vaccine. J Infect Dis 2010;201(1):32-41. ↩︎

Chen CJ, Lin PY, Tsai MH, et al. Etiology of community-acquired pneumonia in hospitalized children in northern Taiwan. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2012;31(11):e196-201. ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Hung HM, Hsieh YC, Huang YC, et al. 2017. Incidence and Etiology of Hospitalized Childhood Community-Acquired Alveolar Pneumonia in Taiwan. In 35th Annual Meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases, ESPID 2017, Abstract ESP17-0099. Madrid, Spain. ↩︎ ↩︎

Wu HM, Wong KS, Huang YC, et al. Macrolide-resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae in children in Taiwan. J Infect Chemother 2013;19(4):782-6. ↩︎ ↩︎

Wu PS, Chang LY, Lin HC, et al. Epidemiology and clinical manifestations of children with macrolide-resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia in Taiwan. Pediatr Pulmonol 2013;48(9):904-11. ↩︎ ↩︎

Jain S, Williams DJ, Arnold SR, et al. Community-acquired pneumonia requiring hospitalization among U.S. children. N Engl J Med 2015;372(9):835-45. ↩︎ ↩︎

Berg AS, Inchley CS, Aase A, et al. Etiology of Pneumonia in a Pediatric Population with High Pneumococcal Vaccine Coverage: A Prospective Study. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2016;35(3):e69-75. ↩︎

Jadavji T, Law B, Lebel MH, et al. A practical guide for the diagnosis and treatment of pediatric pneumonia. CMAJ 1997;156(5):S703-11. ↩︎ ↩︎

Fu LY, Ruthazer R, Wilson I, et al. Brief hospitalization and pulse oximetry for predicting amoxicillin treatment failure in children with severe pneumonia. Pediatrics 2006;118(6):e1822-30. ↩︎

Brown L, Dannenberg B. Pulse oximetry in discharge decision-making: a survey of emergency physicians. CJEM 2002;4(6):388-93. ↩︎

Juven T, Mertsola J, Waris M, et al. Etiology of community-acquired pneumonia in 254 hospitalized children. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2000;19(4):293-8. ↩︎

Tan TQ, Mason EO, Jr., Barson WJ, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcome of children with pneumonia attributable to penicillin-susceptible and penicillin-nonsusceptible Streptococcus pneumoniae. Pediatrics 1998;102(6):1369-75. ↩︎

Mamtani M, Patel A, Hibberd PL, et al. A clinical tool to predict failed response to therapy in children with severe pneumonia. Pediatr Pulmonol 2009;44(4):379-86. ↩︎

Sebastian R, Skowronski DM, Chong M, et al. Age-related trends in the timeliness and prediction of medical visits, hospitalizations and deaths due to pneumonia and influenza, British Columbia, Canada, 1998-2004. Vaccine 2008;26(10):1397-403. ↩︎

Bradley JS, Byington CL, Shah SS, et al. The management of community-acquired pneumonia in infants and children older than 3 months of age: clinical practice guidelines by the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society and the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2011;53(7):e25-76. ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Harris M, Clark J, Coote N, et al. British Thoracic Society guidelines for the management of community acquired pneumonia in children: update 2011. Thorax 2011;66(Suppl 2):ii1-23. ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

W.H.O. 2012. WHO Guidelines Approved by the Guidelines Review Committee. In Recommendations for Management of Common Childhood Conditions: Evidence for Technical Update of Pocket Book Recommendations: Newborn Conditions, Dysentery, Pneumonia, Oxygen Use and Delivery, Common Causes of Fever, Severe Acute Malnutrition and Supportive Care. Geneva: World Health Organization. ↩︎

Lodha R, Kabra SK, Pandey RM. Antibiotics for community-acquired pneumonia in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013(6):CD004874. ↩︎

Lodha R, Randev S, Kabra SK. Oral Antibiotics for Community acquired Pneumonia with Chest indrawing in Children Aged Below Five Years: A Systematic Review. Indian Pediatr 2016;53(6):489-95. ↩︎

Tramper-Stranders GA. Childhood community-acquired pneumonia: A review of etiology- and antimicrobial treatment studies. Paediatr Respir Rev 2018;26:41-8. ↩︎

Vilas-Boas AL, Fontoura MS, Xavier-Souza G, et al. Comparison of oral amoxicillin given thrice or twice daily to children between 2 and 59 months old with non-severe pneumonia: a randomized controlled trial. J Antimicrob Chemother 2014;69(7):1954-9. ↩︎

Bradley JS, Garonzik SM, Forrest A, et al. Pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and Monte Carlo simulation: selecting the best antimicrobial dose to treat an infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2010;29(11):1043-6. ↩︎

Uehara S, Sunakawa K, Eguchi H, et al. Japanese Guidelines for the Management of Respiratory Infectious Diseases in Children 2007 with focus on pneumonia. Pediatrics International 2011;53(2):264-76. ↩︎ ↩︎

Shaughnessy EE, Stalets EL, Shah SS. Community-acquired pneumonia in the post 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine era. Curr Opin Pediatr 2016;28(6):786-93. ↩︎

Ambroggio L, Test M, Metlay JP, et al. Beta-lactam versus beta- lactam/macrolide therapy in pediatric outpatient pneumonia. Pediatr Pulmonol 2016;51(5):541-8. ↩︎

Nascimento-Carvalho CM, Xavier-Souza G, Vilas-Boas AL, et al. Evolution of acute infection with atypical bacteria in a prospective cohort of children with community-acquired pneumonia receiving amoxicillin. J Antimicrob Chemother 2017;72(8):2378-84. ↩︎

Dimopoulos G, Matthaiou DK, Karageorgopoulos DE, et al. Short- versus long-course antibacterial therapy for community-acquired pneumonia : a meta-analysis. Drugs 2008;68(13):1841-54. ↩︎

Haider BA, Saeed MA, Bhutta ZA. Short-course versus long-course antibiotic therapy for non-severe community-acquired pneumonia in children aged 2 months to 59 months. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008(2):CD005976. ↩︎

Greenberg D, Givon-Lavi N, Sadaka Y, et al. Short-course antibiotic treatment for community-acquired alveolar pneumonia in ambulatory children: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2014;33(2):136-42. ↩︎

Hamano-Hasegawa K, Morozumi M, Nakayama E, et al. Comprehensive detection of causative pathogens using real-time PCR to diagnose pediatric community-acquired pneumonia. J Infect Chemother 2008;14(6):424-32. ↩︎

Feigin RD. 2009. Bacterial pneumonias. In Feigin & Cherry's textbook of pediatric infectious diseases. Philadelphia, PA : Saunders/Elsevier. ↩︎

Lin TY, Hwang KP, Liu CC, et al. Etiology of empyema thoracis and parapneumonic pleural effusion in Taiwanese children and adolescents younger than 18 years of age. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2013;32(4):419-21. ↩︎

Wei SH, Chiang CS, Chen CL, et al. Pneumococcal disease and use of pneumococcal vaccines in Taiwan. Clin Exp Vaccine Res 2015;4(2):121-9. ↩︎

Wei SH, Chiang CS, Chiu CH, et al. Pediatric invasive pneumococcal disease in Taiwan following a national catch-up program with the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2015;34(3):e71-7. ↩︎ ↩︎

Chiang CS, Chen YY, Jiang SF, et al. National surveillance of invasive pneumococcal diseases in Taiwan, 2008-2012: differential temporal emergence of serotype 19A. Vaccine 2014;32(27):3345-9. ↩︎

Pallares R, Capdevila O, Linares J, et al. The effect of cephalosporin resistance on mortality in adult patients with nonmeningeal systemic pneumococcal infections. Am J Med 2002;113(2):120-6. ↩︎

Wang SR, Lo WT, Chou CY, et al. Low rate of nasopharyngeal carriage and high rate of ampicillin resistance for Haemophilus influenzae among healthy children younger than 5 years old in northern Taiwan. J Microbiol Immunol Infect 2008;41(1):32-40. ↩︎

Ma YJ, Wang SM, Cho YH, et al. Clinical and epidemiological characteristics in children with community-acquired mycoplasma pneumonia in Taiwan: A nationwide surveillance. J Microbiol Immunol Infect 2015;48(6):632-8. ↩︎ ↩︎

Ambroggio L, Taylor JA, Tabb LP, et al. Comparative effectiveness of empiric beta-lactam monotherapy and beta-lactam-macrolide combination therapy in children hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia. J Pediatr 2012;161(6):1097-103. ↩︎

Leyenaar JK, Shieh MS, Lagu T, et al. Comparative effectiveness of ceftriaxone in combination with a macrolide compared with ceftriaxone alone for pediatric patients hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2014;33(4):387-92. ↩︎

Williams DJ, Edwards KM, Self WH, et al. Effectiveness of beta-Lactam Monotherapy vs Macrolide Combination Therapy for Children Hospitalized With Pneumonia. JAMA Pediatr 2017;171(12):1184-91. ↩︎

Cevey-Macherel M, Galetto-Lacour A, Gervaix A, et al. Etiology of community-acquired pneumonia in hospitalized children based on WHO clinical guidelines. Eur J Pediatr 2009;168(12):1429-36. ↩︎

Bradley JS, Byington CL, Shah SS, et al. Executive summary: the management of community-acquired pneumonia in infants and children older than 3 months of age: clinical practice guidelines by the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society and the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2011;53(7):617-30. ↩︎ ↩︎

Clsi. 2008. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. CLSI document M100-S18. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. ↩︎ ↩︎

Taiwan Centers for Disease Control. Report of drug resistance surveillance of Streptococcus pneuomoniae in 2016 in Taiwan. Accessed Jan 27, 2018. ↩︎ ↩︎

Cho YC, Chiu NC, Huang FY, et al. Epidemiology and antimicrobial susceptibility of non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae in otitis media in Taiwanese children. J Microbiol Immunol Infect 2017. ↩︎ ↩︎

Hsu SF, Lin YT, Chen TL, et al. Antimicrobial resistance of Moraxella catarrhalis isolates in Taiwan. J Microbiol Immunol Infect 2012;45(2):134-40. ↩︎

- Red Book, 30th Edition (2015). American Academy of Pediatrics.

Okazaki N, Narita M, Yamada S, et al. Characteristics of macrolide-resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae strains isolated from patients and induced with erythromycin in vitro. Microbiol Immunol 2001;45(8):617-20. ↩︎

Parrott GL, Kinjo T, Fujita J. A Compendium for Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Front Microbiol 2016;7:513. ↩︎

Okada T, Morozumi M, Tajima T, et al. Rapid effectiveness of minocycline or doxycycline against macrolide-resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection in a 2011 outbreak among Japanese children. Clin Infect Dis 2012;55(12):1642-9. ↩︎

Poyhonen H, Nurmi M, Peltola V, et al. Dental staining after doxycycline use in children. J Antimicrob Chemother 2017;72(10):2887-90. ↩︎

Lee H, Yun KW, Lee HJ, et al. Antimicrobial therapy of macrolide-resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia in children. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2018;16(1):23-34. ↩︎

Carrillo-Marquez MA, Hulten KG, Hammerman W, et al. Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia in children in the era of community-acquired methicillin-resistance at Texas Children's Hospital. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2011;30(7):545-50. ↩︎